“We are concerned that these schools are being gutted both of instructors and custodial staff without regard to the long-term consequences on students and the operations of the schools,” lawyer Jacqueline De León said. “We are worried this will continue to happen and happen again.”

The lawsuit contends that financial aid has been delayed at Haskell, while at SIPI, badly discolored water is coming out of the showers in students’ dorms because no maintenance workers are left to fix such problems. One residential building was without power for 13 hours, according to the filing.

Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe of New Mexico and former interior secretary in the Biden administration, has blasted the upheaval at Haskell and SIPI. The current administration, she said, doesn’t “understand that the U.S. has a trust responsibility to Indian Country, to tribal nations, for the education of their children.”

Indeed, treaties from the late 1700s require the government to provide that education. Restoring some positions “doesn’t undo the disruption and chaos” the terminations have caused, Haaland added.

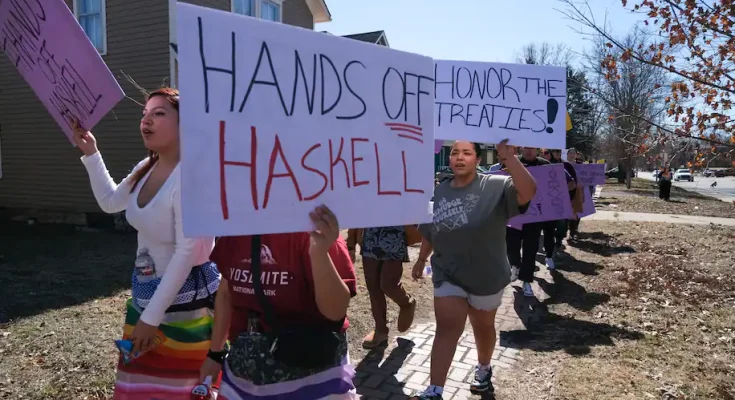

The Haskell community held another event Friday evening, with mixed reactions to the news that some staffers would be rehired. The financial aid specialists and custodial workers are not expected to be.

“It’s a bittersweet moment,” said De’Ara Dosela, a senior from the White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona, who organized the protests.

The university has seen historic enrollment increases as well as controversies in recent years. It serves nearly 1,000 students from nearly 150 tribal nations, including those from remote reservations who otherwise might not be able to afford to attend college. Critics have focused on the school’s low graduation rate.

“Our students are going to class with no teachers to teach them. No people to feed them in the dining hall. They cut tutors, for Christ’s sake. Who does that?” asked Kasey Flynt, the foundation’s director of development.

Senior Tyler Moore, a Kansas resident and member of the Cherokee tribe of Oklahoma, told those gathered that he had lost two teachers and a cherished mentor in the Trump administration’s purge. He first worried his graduation this spring would be derailed and his degree in Native American studies delayed. Now he has broader concerns — for all Native Americans.

“There’s a fear we could go backwards,” Moore said. “To a place where the U.S. goes back to their darkest tendencies.”

Within higher education, Haskell and SIPI are unique. They serve just Native Americans and Alaska Natives and are the only postsecondary institutions directly operated by the Bureau of Indian Education, which is why they were vulnerable to the federal cuts.

“Instructors are coming to class but not being paid,” said sophomore Cheryl Jim, a Navajo from Gallup who is majoring in geospatial information technology. “We’re still coming to class, but the setting isn’t right. The mood is gloomy. Nothing’s happening. That spark isn’t there anymore. … We don’t know what’s going to happen.”

SIPI was established just over half a century ago. Haskell, by contrast, dates to 1884. Originally the United States Indian Industrial Training School, Haskell was one of hundreds of Indian boarding schools operated by the government to assimilate Native Americans into White society by eradicating their culture and languages.

Children as young as 4 were removed from their families and sent to the campus in Lawrence, about 40 miles west of Kansas City. The youngest were famously known as the “Haskell babies” in the 1880s. Students were stripped of their clothes, and their long hair was cut. Speaking a tribal language could lead to a beating.

Haskell eventually grew to be one of the largest Indian boarding schools in the country, with at least 146 students dying there between the late 1890s and mid-1930s, a Washington Post investigation found last year. Yet from its cruel beginnings, the institution eventually transformed into a university that’s now a source of deep pride for Native Americans.

Marisa Mendoza, the newly arrived dean of students who was terminated in February and then rehired Thursday, said the uncertainty of the past month has been difficult for everyone.

“It triggers that feeling of being ‘less than,’ the feeling of ‘here we go again,’ something is happening to us and our people, like we don’t matter,” she said.

Though enrollment has increased in recent years, Haskell faced intense scrutiny in 2024 after federal reports and congressional testimony revealed that the university, along with BIE and Interior officials, did not investigate student and staff reports of harassment, bullying, theft and sexual assault by administrators. The university has also had high turnover in its leadership, testimony by Interior officials noted.

Kansas Republicans in Congress — Sen. Jerry Moran and Rep. Tracey Mann — have introduced a bill that would move control of the university to its board of regents, saying the students deserved better than the “inefficiency and mismanagement and neglect they face under the current governance system.”

Since the firings, the town of Lawrence has rallied around the school. A local sign company donated a “Hands Off Haskell” banner for protests. A nearby tribe is trying to contract a cleaning company to cover for 13 custodians who were dismissed.

And when toilet paper ran low in campus buildings and administrators were having trouble using Haskell’s federal credit cards, a call went out in a local Facebook group. The school was quickly inundated with rolls.