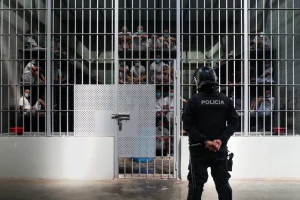

Human rights organizations say the message presented by videos posted by Bukele is clear: This is what awaits those deported from the United States to El Salvador.

The video, posted on social media by Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele on Sunday, is tightly edited and set to dramatic music. It begins with drone footage of three planes on the tarmac, surrounded by rows of soldiers and police in riot gear.

The video has been viewed more than 21 million times on Bukele’s X account in less than 48 hours, drawing attention to the harsh treatment of prisoners in El Salvador.

Human rights experts say Bukele shared the video to reinforce his strongman image and promote his prison system as a model for combating crime globally. But the footage itself, they argue, shows clear signs of human rights violations.

It was troubling, she added, that the video prominently displayed the migrants’ faces without confirmation of their criminal record.

The Trump administration faces accusations of defying a federal judge’s order to stop deportations under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which allows migrants to be expelled without a hearing.

For Noah Bullock, the executive director of the Central American human rights organization Cristosal, the video was “reminiscent of penal colonies from the long ago time of empires where people were sent away as a way to suspend their rights and permanently remove them from society.”

Bukele’s social media strategy

El Salvador, though, also opened its prisons to social media influencers and travel content creators. One YouTube video has over 71 million views; another has 55 million views.

Influencers are how “the regime propagates its propaganda,” Bullock said, adding that “They activate and pay a swarm of social media mercenaries to reproduce the image of themselves that they want to sell.”

Many of the images featured in the videos are recurring, said Sonja Wolf, a professor of political science at Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) in Mexico.

Bukele also uses social media to defend his use of mass incarcerations. “Put them all in jail so they can’t kill anymore,” he said in an X post in February 2024 while explaining how he made El Salvador the “safest country in the Western Hemisphere.”

An opaque system

Bukele, who won a second five-year term in 2024 by a landslide, has one of the highest approval ratings of any world leader, due in large part to his crackdown on gangs and cartels.

Bukele declared a state of emergency in 2022, followed by mass arrests of suspected gang members and the rapid construction of CECOT. In his time as president, Bukele has lowered the country’s homicide rates, once the highest in the world, and has encouraged other Latin American countries to follow his lead.

But human rights experts, such as Bullock, are quick to point out that Bukele’s prison system, especially CECOT, is “one of the most opaque prison systems in the hemisphere,” adding that “they only show images they want to share.”

According to the World Prison Brief, a United Kingdom-based database on prisons around the world, there are 25 prison facilities in El Salvador, with an official capacity of 67,289 inmates.

El Salvador’s prison population has surged in the past 25 years, and even the rapid construction of CECOT hasn’t been able to keep up with the level of imprisonment in the country. Inmates have increased from 7,754 in 2000 to 37,190 in 2020, to roughly 109,519 in 2024, according to the Brief. The prison occupancy rate is almost at 163 percent.

“There are prisons in the country where overcrowding is such that people have to take turns standing and sitting,” said Bullock. “Human rights organizations have documented systemic torture and lack of access to families and lawyers in these places.”